Features Overview

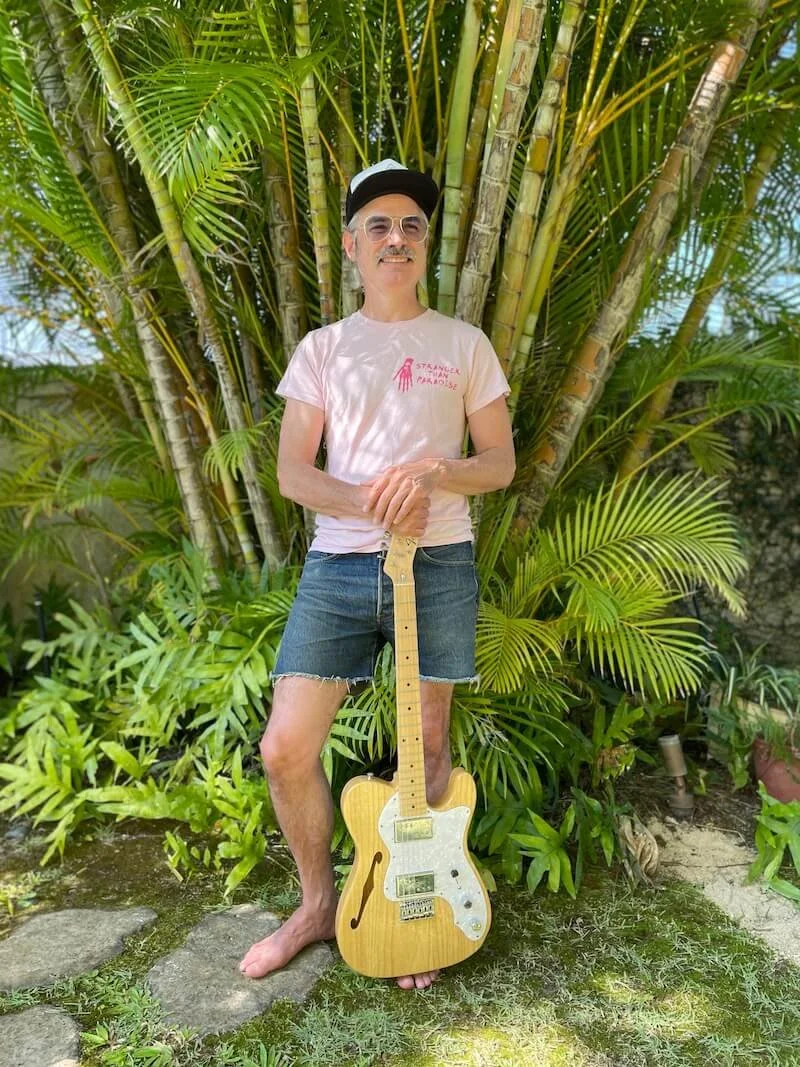

Photo courtesy of Sanae Yamada

Catching Up With Rose City Band

Though the grooves of Rose City Band’s Garden Party go down easy, when he was coming of age in Wallingford, Connecticut in the 1980s, Ripley Johnson defined himself by what he hated. “Being an adolescent you’re just against everything, so we were against all of the synth pop and ’80s haircuts,” says Johnson. “Everything was neon and there were yuppies and Reagan.” As a teenager, Johnson longed for more adventurous sounds, drawn to punk bands like Black Flag and JFA through his love of skateboarding and Thrasher Magazine.

“When you grow up in a small town you’re finding clues everywhere about the counterculture,” said Johnson. “It was really an act of sleuthing.” Punk rock shifted to a fascination with the 1960s as Johnson began experimenting with psychedelics and the music that came along with them. Indulging in Jimi Hendrix and Neil Young was a form of resistance. “Sticking it to the man,” says Johnson.

Inspired by a friend, Johnson left Wallingford to chase his dreams of living on the West Coast. “I got on a Greyhound bus,” Johnson explains. “They were running this special for a while. I’m pretty sure it was $69 to go anywhere in the country.” So, Johnson saved up his money, spent three days on the bus and found himself in California where he enrolled at UC Santa Cruz and formed his first band, Botulism.

Heavily influenced by Blue Cheer, the Stooges and the Japanese label Psychedelic Speed Freaks, Botulism cranked their amplifiers to the maximum volume, and cleared rooms with their deafening noise. “Looking back, I’m kind of proud of my younger self,” said Johnson. “I think we were pretty terrible in a lot of ways, but we were committed. We didn’t care that everyone left.”

Once Johnson graduated, Botulism moved to San Francisco, where they released one 7” record and found little success. After Botulism, Johnson’s music taste shifted to free jazz, minimalist music and Krautrock. The repetitive quality of these genres led Johnson to a musical epiphany. “There’s some music that people just respond to intuitively because it’s a primal thing,” Johnson says. “And so, I thought if I find non-musicians, I can teach everyone a chord and experiment with that.”

The group of non-musicians jammed for a couple years but never played a show. Uninterested in making an album or playing live they went their separate ways. Still passionate about the primitive project, Johnson recorded and released a solo 10” record titled Wooden Shjips which became the name of his first major band.

Johnson lost his job in San Francisco’s tech industry during the 2008 financial crisis. The solution, and artistic challenge to his unemployment was to form a new band that “said yes to everything,” said Johnson. So, he put Wooden Shjips on the backburner and started Moon Duo with his wife, Sanae Yamada.

Their records well received, Moon Duo hit the road. “It was just the two of us, and we could travel pretty cheaply,” said Johnson. “We went to Finland and Estonia. We went to Moscow, Ukraine and Sardinia. Just all over.” After touring consistently for a few years, Johnson and Yamada settled in Portland, Oregon in 2012. Johnson was drawn to Portland’s gentle qualities compared to San Francisco.

“There’s a bigger sense of the natural world even if you’re living in a neighborhood,” said Johnson. “It’s much greener.”

“For a while I just kind of hid behind fuzz,” said Johnson of the music he had created over the years. “I was really into fuzz and distortion. More obscure vocals and loud music.” Over the years, as his projects mellowed, Johnson longed for a new sound. “I felt that there was a part of my musical personality that I hadn’t expressed yet,” said Johnson. “I wanted to do something with a little twang in it.”

“When I was younger I had more energy, everything was fast and groovy,” said Johnson of songwriting. “The Rose City Band stuff comes from just strumming the acoustic guitar.” Rose City Band is the fruit of Johnson’s appreciation of music and eclectic taste. “I’m a huge Neil Young fan from childhood. But also the Grateful Dead, The Stones, their more pastoral vibe, and The Band, Bob Dylan,” said Johnson. “And then I’m really into country like Waylon

Jennings, Willie Nelson and Lucinda Williams, it’s just a side of me that I really respond to in music and something that I’ve always wanted to do.”

For years Johnson longed to form a country rock band. Due to the pandemic, he released three albums as Rose City Band before ever playing a live show. As restrictions loosened, Johnson recruited a handful of local musicians to perform live as Rose City Band. “We got really tight and we played this Mississippi Studios show. Afterwards Sanae was like, ‘You did it, you got your country rock band.’” The sound in Johnson’s head had come to life, inspired by Portland summers. “The feeling of going for a bike ride or sitting on your porch,” said Johnson. Johnson’s attitude towards life is reflected in his music.

“He’s got a very zen vibe to him,” said Dustin Dybvig, drummer of Rose City Band. “I look up to his calmness, especially on the road.”

“Initially I didn’t love touring,” Johnson says. “I’m not super into being the center of attention. I still get anxious about playing on stage and I don’t really want to be in the spotlight.” There is uncertainty with live performances. “It’s sort of akin to throwing a party,” said Johnson. “You’re not sure if people are going to come to your party or not.” Performing with other people helps Johnson overcome his anxieties. “It’s like a safety net,” says Johnson. “Everyone’s carrying the load.”

Johnson especially feels a sense of security when performing as Rose City Band. “The guys in the band are all really enthusiastic about music, they all want to play,” said Johnson. “They come alive on stage and get this energy that is just so contagious.”

Rose City Band is composed of five musicians, the largest group that Johnson has performed with. “It takes the pressure off because everyone is contributing,” Johnson says. “If you’re well-rehearsed and everything is going well and you have good material, you have this confidence that you’re going to go out and crush it.”

“You’re a crew,” Johnson says of being in a band. “You develop that the more you play, especially when you’re on tour. You can rehearse every week for a year and you’ll never get as tight as doing a one or two week tour. You get so good so quickly because everyone is responding to each other, making micro adjustments all the time and bonding in a way that I think is really special.”

“The live show is so ephemeral, it’s a different type of beauty,” Johnson says. “I don’t like recreating the record live. I find it’s often better, especially live, if someone brings something you hadn’t thought of like a different bass line or keyboard sound. It keeps it fresh to me.”

While Johnson has grown to appreciate touring, his favorite part of being a musician is making albums. “Records have been so important to me in my life,” Johnson says. “It’s almost like a drug. I rely on records to cheer me up or calm me down.”

“Making the record is one thing, and playing live is a completely different thing,” Johnson says. “The record stands as what it is. That’s me trying to get the sound that’s in my head exactly how I want it on the record and indulging myself.”

The live band is a whole different experience. “I don’t feel like I really know what I’m doing most of the time and I embrace that,” Johnson says. “A lot of the music that I like is outsider kind of music. Private press, weird music that was never successful for whatever reason. Or was just done in a different way and appreciated later.” Johnson tries to retain the amateur, outsider sound in his music. “I do just by virtue of not being a great musician,” Johnson says. “I can’t do everything, but I can do these things. I record most of the stuff at home, so it hopefully retains a humble, homemade sort of feel.”

Garden Party is a summer album and Johnson looks forward to performing the songs live. “I feel like I really lucked out,” Johnson says of the touring band. “Everyone’s fired up in this band, just having a good time.”

Photo by Roman Koblov

Brueder Selke’s Sebastian and Daniel Selke

Childhood has a profound impact on the way that humans navigate the world. It shapes personalities, fosters curiosity and acts as the road map for the long journey called life. In the case of Sebastian and Daniel Selke, of Brueder Selke, the influence of childhood has fostered their creative spirit and aided the conception of their most recent release with Midori Hirano, “Split Scale.”

Coming of age in a small, walled off city under Soviet rule is not a universal experience but for the Selkes, it was all they’d ever known. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, the brothers were faced with the task of unlearning Soviet propaganda and expanding their view of the world. “Split Scale” references this time in the brother’s lives, while also building on themes of connectivity and childlike instinct for play and discovery through its experimental adaptation of the western scale. The use of manipulated sounds and spontaneity challenges the boundaries of classical music, while building on the fundamental teachings from the artist’s musical backgrounds.

Off Shelf: You recently released an album with Midori Hirano titled ‘Split Scale,’ can you tell me a little bit more about how this collaboration came to be?

Sebastian Selke: We have known Midori for a very long time. I think since the beginning of our little festival Q3Ambientfest, a mini festival for ambient music, neoclassical and a meeting point for encounter and exchange with other artists. Our main goal was to reach out to other artists because of our past in East Berlin where we were always surrounded by a wall. That was the same with Midori, especially because she came from the so-called Far East, from Japan. We decided after the pandemic to do our first real collaborative album with an artist and Midori directly popped up. She’s very versatile and she knows a lot of aspects of modern or experimental music from the classical point of view, so she was an ideal partner.

OS: Split Scale follows the scale of A to G. How did you decide on this concept and what was the process like as you began to create your compositions and collaborate with Midori?

SS: The idea was really to start from a blank project. Our solo project has always focused on the past, especially our childhood where everything started, and our youth time after the fall of the wall. We were present in the classical world but there was always a certain point where the repertoire was finished, and this was our limitation. We noticed that Midori had almost the same path through her development as an electronic musician with classical aspects. With her, we wanted to start from a childhood moment where everything was more new. We decided that the western scale was a good starting point.

It’s a little funny because as an East German we had to learn [the western scale]. But still, here and there were these moments where we couldn’t resist moving toward the western world. For example, the Communist Party was very against Christianity and crosses but their main TV tower, centered in the main part of the capitol, made a cross with its reflection when the sun was shining. With our humor, we like the ironic things that came through. It’s not possible to divide a whole population of people; there will always be a gap where you can look through and find your way.

OS: Is there a song from the album that’s your favorite or one that you’re most proud of?

SS: I don’t want to say that we always do full concept albums, but there is a bit of truth in it because it’s a development. We like to tell a bit of a story because these days everything is so fast and there is no time to really listen to one another. We have this especially [in Germany] with our politics; they don’t ever listen to each other and they don’t ever give each other the time to understand the arguments. Split Scale is more of a story in the way the album follows track by track. It’s also a bit of the classical movement because classical music needs time as well. Time is our main aspect over which track is our favorite.

OS: How does Split Scale compare and contrast with your previous works?

SS: Whether “undercover” as CEEYS or now under our real name, we have always dealt with personal topics in our albums. At the same time, we keep coming across wonderfully original concepts at our Q3Ambientfest. The highlights were always the spontaneous improvisations with one artist or another. Most of them practically unrehearsed, nevertheless very intuitive and genuine. Split Scale is the first attempt – with an artist we find extremely inspiring – to capture and record this magical collaborative moment. Conceptually, the album is therefore not directly a look back at our musical beginnings in a thin-walled East German Plattenbau, but it does follow an innocent childlike instinct for play and discovery.

OS: From the listening perspective, what are you hoping that your audience takes away from this album?

SS: This album is a peak point for our releases. We took a lot of time to release our own story because it was difficult to find ourselves. We changed our name from our alias CEEYS because everybody was saying, “you have so many Spotify followers,” but that’s not our goal. I don’t want to collect just listeners. It’s beautiful, of course that it’s working but behind these tracks lies so much more. It’s the story of two brothers who come from an isolated place of no return.

The [German Democratic Republic] told us when I was nine years old that the wall would stand there for the next hundred years. We were so flabbergasted that it was possible to break not only through the wall and be able to release music but to invite like-minded people to do an album together. We came from a communist world and we saw the other world, the western hemisphere, as the enemy. In school, they told us how bad the western world was and that children had nothing to eat. When you have no experience, you believe what they tell you.

I have a daughter now who is only five years old, and I have to give her this open mindedness from the very start to find her own way because when we were children we had a straight line.

People now, with technology, are drilled to be focused in small packages. Maybe if everyone would learn an instrument, they would learn how important it is to take the time to learn something and to understand the other side. To find your own way through all the stories and understand what the other wants to say.

OS: What are some of your musical influences?

SS: From the very beginning, our approach to composition has been all about diversity, diversity and a tolerant plurality. What this means is that with our knowledge of vibrant textures and repeating structures in minimalist songwriting, we create an experimental yet accessible tonality of manipulated acoustic and electronic music between avant-garde and pop. We try to intelligently incorporate spontaneous and prepared organic and synthetic elements of classical and impressionistic chamber music and free jazz, ambient pads and cinematic sound effects, as well as refined chill-out songs and complex abstract noise.

Daniel Selke: Our music reflects the myriad sounds that we have encountered in our lives. Early influences such as Johann Sebastian Bach & Claude Debussy are just as recognizable as the East German group City with Georgi Gogow on violin, and Frank Fehse’s synthesizer duo Key. The names City and Key can be seen as components of the neologism CEEYS. Further inspiration came from, for example, Arvo Pärt & Philip Glass, Arthur Russell & Allen Ginsberg, as well as Hildur Gudnadóttir & Nils Frahm, and Colin Stetson & Sarah Neufeld…

SS: In the 1990s, we also discovered a generation of East German artists who had explored the intersection between music, art and science. Be it Frank Bretschneider, who founded the influential underground band AG Geige in 1986, or Carsten Nicolai as Alva Noto: the fluid intersection between complexly interwoven rhythmic structures and strict reductionism, as well as the analytical view of individual elements, fascinate us to this day.

DS: We also like the approach of the brothers Robert and Ronald Lippok. Their band Ornament & Verbrechen had a defining influence on German subculture of the 1980s. Their work on electronic instruments that were difficult to obtain in the GDR and often had to be borrowed or converted from existing equipment was driven by their love of experimentation. And it wasn’t just because of the ubiquitous lack of materials, they also created an alternative to the prevailing rock aesthetic.

OS: What can people expect from Brueder Selke in the future?

SS: Tying into these early musical ideas from our childhood, we are planning our first music book. Presented will be compositions that through their simplicity will be accessible to everyone. We’ve also included an extra booklet – with a second copy of the music – so you can approach the music in pairs. The fun of playing and “listening to each other” also plays a central role here.

DS: Parallel, we are currently organizing the ninth edition of our festival, out of our own pocket. Unfortunately, the necessary massive budget cuts also in the cultural sector mean that the previous support from the city of Potsdam is no longer possible.

SS: Following our purely musical collaboration with Midori, we are also very excited about an invitation from the artist Sven Sauer with whom we will be creating an interdisciplinary installation for the first time. The work could possibly also result in a new album.

Daily Emerald/Kemper Flood

‘Just become the weather,’ a look at the life and art of Leonardo Drew

Bantering back and forth like two old friends, Leonardo Drew and Jordan Schnitzer recollect old memories and riff off of each other as they saunter through the heavy metal doors of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on campus. Led by museum staff, the pair are escorted up a daunting flight of marble stairs. At the top, Drew’s mouth spreads into a wide smile as he is confronted with his work, “215B.”

“215B” is the first visible work of art in the exhibition Strange Weather, which opened at the JSMA on Oct. 21. Sprawling across three museum walls, the work appears to extend an arm and invite the viewer in for a better taste.

“I believe these works should act as mirrors,” Drew said of his art. “There’s no way you won’t find some through-line that we all are part of.”

Drew is a Brooklyn-based artist best known for his large-scale, abstract work. Born in Tallahassee, Flo. but raised in the projects of Bridgeport, Conn., Drew knew he was an artist at a young age.

“Even though I’m named Leonardo and my mother says she knew for whom she named me, she did not,” Drew said to a captivated audience in a lecture held at PLC on campus. “Only sometime later, after many beatings for being named Leonardo in the projects, the nuns told me, ‘Oh, like Leonardo Da Vinci?’ and I was like ‘There’s another Leonardo?’”

Despite his mother unknowingly bestowing him an artist’s name, she did not encourage his early artistic endeavors. “My mother is a strong spirit, definitely an influence, but she did not understand,” Drew said. “You got to understand that if you’re growing up in the projects and someone in school gives you a test paper and you start drawing all over it, it’s time to stop you from doing that.”

But Drew didn’t stop. He was scouted by DC and Marvel Comics as a teenager, the result of having his drawings published at age 13.

“When Marvel and DC approached me, it seemed like the correct thing to do, to use your talent to get out of the projects,” Drew said. “Once I saw Jackson Pollock though, that was canceled.”

Pollock’s work inspired Drew to transition from drafting and two-dimensional art into a world of visceral three-dimensional art. Drew attended Parsons School of Design in New York for two years before transferring to The Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. At Cooper Union, Drew met Jack Whitten, a professor who he describes as both a father and mentor figure.

“What he brought to the table was this undying curiosity to continue,” Drew said. “That even though you were not accepted in the mainstream, there was still a connection to a larger world. It seemed to not be inclusive but actually, there are no barriers when it comes to art."

The year was 1985 and Black artists like Drew and Whitten were given few avenues of representation. At the time, the expectation was that they would teach or travel, but rarely find success in the mainstream.

“If you’re a Black artist, there’s a door that you have to go through,” Drew said. “I never really believed that. It was a different kind of work that I was determined to change and challenge.”

“Great art grabs you and shakes you and makes you think,” Schnitzer said, gazing up at “215B” in his gallery. “So he’s already won half the battle.” Schnitzer went on to cite Drew’s “genetic predisposition towards aesthetic” as the other half of his triumph in surviving the world of professional artists.

Drew has made a name for himself in the art world and proven that his bold and abstract art has a place in the mainstream. His works have been shown across the globe, and in notable museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York and the Tate in London.

Recently, Drew has spent time traveling in Peru and China, which has influenced him to utilize new techniques, such as the inclusion of color, in his works. “This planet is full of so much,” Drew said. Travel informs his artistic vision, and he acts “as an antenna receiving new information” in the places he visits.

Drew is constantly working and reworking his art, taking things that are “finished” and creating the next piece. “When you get comfortable, tie your hands and try again,” Drew said of his experience making art. “There is no such thing as a mistake.”

As far as legacy, Drew is not concerned with his impact on the world, so much as his desire to make art and his purpose as an artist. “These works can go on to disintegrate,” Drew said. “But for me they were important.”

At age 62, Drew is approaching a phase of life in which most people contemplate retirement, though he has no plans of seizing to make art. “I am absolutely an addict,” Drew said. “Making, making, making to the point where my hands and everything are starting to give problems.”

Despite his extensive career and the physical implications of being an aging artist, Drew prevails. “I need to continue to challenge myself,” he said. “That’s what keeps life interesting for me.”

Drew’s work “215B” is available for viewing at the JSMA until April 7.